A rush and a push, etc………..

A recent article in the Manchester Evening News has reported on the re-committal rate of prisoners released from Strangeways prison, with an apparent fifty-five percent of prisoners offending again within twelve months.

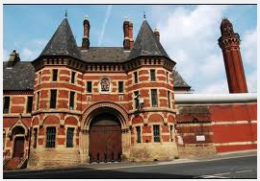

The words of Justice minister Jeremy Wright, when he speaks of a cycle of “prison, release, offend and back to prison”, could have come from the 1870s. One difference being, that some women offenders didn’t wait twelve months before returning to prison. Short sentences and repeat offending were constant topics of debate in the late nineteenth-century. England’s prison system had, according to the Whiggish interpretation of history, been reformed along humanitarian grounds, in a move away from the Bloody Code of the eighteenth century (check out Lucy Williams’ blog on this – http://waywardwomen.wordpress.com/2013/04/30/no-place-for-a-lady-back-to-the-victorian-penal-system/ ) and Strangeways was a model prison of the Victorian era, built to replace the ageing New Bailey Prison in Salford and opened in 1868. Yet since its opening it became, like its predecessor, a revolving door, through which passed intemperate women time and time again, serving sentences of only a few days for drunkenness or other petty offences before returning.

For example, from Salford, between 1870 and 1874, total female committals almost doubled, from 439 to 851. 358 individuals were committed in 1870, compared to 631 in 1874, showing that the number of women committed multiple times increased over the period (19% in 1870, 26% in 1874). Most of these were committed twice, but the number of women committed three or more times also increased. Of course, some women were more regular visitors than others. For example, when Julia Whelan received 14 days for drunk and riotous behaviour in Salford in 1874 it was her forty-seventh committal – but not necessarily her forty-seventh offence. Top marks, however, go to Sarah Ann Lee, aka Shannon, who was committed to Strangeways for seven days in July 1870 for being drunk and disorderly in Whit Lane – her eighty-first committal. Granted, these are exceptions, but not particularly rare ones.

My current favourite politician, JT Tomlinson, at one time chairman of the Visiting Justices to Strangeways, is often to be found discussing what he perceived as the inefficiency of the prison system towards both male and female offenders. In one instance he states that “It really was a farce to send prisoners to goal for such a short term. They merely went there to be cleaned and made decent, and when they were turned out they resumed their career of vice and debauchery.” Plenty of food for thought here.

Different magistrates had difference methods of dealing with drunkards, in particular. One felt that the meals provided to prisoners on longer sentences were more generous than for shorter periods and the “rigorous diet” they had during a shorter stay was more of a punishment. One felt that drunkards should be sent to reformatories rather than prison (a move made later on in the century).

Although this is a rather brief analysis, it is sobering (no pun intended) to realise that nearly 150 years after the Quarter Sessions at which this was discussed, the deterrent or reformatory effect – or lack of – of short sentences and re-offending is still relevant and being discussed. Perhaps Jeremy Wright would do worse than to examine Victorian concerns over the issue, something I’ll be doing over the coming months.